The Billion Dollar Revenue Club

Move over Unicorns, Decacorns, and Centaurs. There's a more important club in town.

Welcome to issue #47 of next big thing.

One refreshing aspect of market cycles is the ability to re-evaluate the metrics and goal posts that companies should be aiming for.

A decade ago, venture capitalist Aileen Lee coined the term Unicorn, referring to companies that are valued at over $1 billion either in the public or private markets or at exit. Back then, in late 2013, there were 39 members of the “Unicorn Club” which consisted of companies that had been started since 2003. There are many great insights from that original post about Unicorns, and at the time, the $1 billion valuation served as a useful goal post for “success” for venture-backed technology companies.

Over the past ten years, an astounding number of companies achieved the $1 billion valuation mark in the private and public markets. Today, according to data sources such as PitchBook and CB Insights, there are over 1200 global Unicorn companies. PitchBook, which counts both public and private companies, lists almost 100 companies that are Decacorns, a term used to describe companies with valuations over $10 billion, with CB Insights only including private companies and counting just over 50 Decacorns. And many of the companies that achieved Unicorn status over the past decade went public or got acquired, leading to liquidity for their founders, employees, and venture investors. 182 companies valued at over $1 billion went public in the U.S. in 2021, according to Crunchbase, though of course many of them are no longer trading at over a $1 billion market cap.

Culling of the Unicorn herd

Which brings us to today, and the unfortunate reality of what we’ll see over the next few years. Many of the companies that achieved Unicorn status in the private markets do not have businesses that merit their $1+ billion valuation. There will be a culling of the Unicorn herd, with some of these companies shutting down, others raising capital or exiting at valuations below $1 billion, still others who survive on their cash but don’t build businesses that merit future venture funding, and, hopefully, quite a few making it to the promised land of a multi-billion-dollar exit one day.

What we’ll realize is that the Unicorn term, while helpful in thinking about the companies that define “success,” was not the right goal for companies to seek. Venture funding and company building should never have been about achieving a $1 billion valuation in the private markets. We will realize the massive difference between being valued and actually exiting at an enterprise value north of $1 billion.

So what is, then, the right goal post for companies to think about? Venture firm Bessemer coined the term Centaur to refer to SaaS companies that achieve more than $100 million in annual recurring revenue (ARR). But what we see in the public markets is that $100 million of ARR is not enough to build a public SaaS company. A quick scan of venture firm Meritech’s public SaaS comparables table shows that there are only 6 public SaaS companies with ARR under $200 million, and each of them is trading at an enterprise value below $1 billion.

At Footwork, we think about a different goal post in our ultimate analysis of a new investment:

Can the company get to over $1 billion of annual revenue?

Why? To give you some more insight into how we think, one of the hardest questions to answer when evaluating a new investment is “how large can this company become?” And yet, it’s in many ways the most important question to have a perspective on as a venture capital investor. Our industry’s returns are based on the power law: the reality that a small handful of massive companies and winning investments end up contributing to the vast majority of gains. This was of course the original premise behind the Unicorn labeling as well.

In our decision-making process, we continually try to ask ourselves: “can this company become ‘one of the ones’?” One of the small handful of companies that will become enormous? One of the ones that will return multiples of our fund if it works? One of the ones we just have to be a part of?

If a company can get to more than $1 billion of annual revenue, it has a good chance of being “one of the ones.” In general, the higher the gross margins and the more recurring and predictable that revenue is, the higher the enterprise value as a multiple of revenue. The faster the revenue is growing and the more profitable the company is, the higher the enterprise value. The more capital efficient the path a company takes to $1B+ of revenue, the better the return on investment is likely to be.

But, if we lead a company’s Seed or Series A round, and that company goes on to generate more than $1 billion in revenue, it’s likely to be a fund-returning investment for us at Footwork. The median public SaaS company currently trades at a 6X multiple of next twelve months (NTM) revenue. So let’s say simplistically that an average SaaS company trades at a $6B market cap when projecting $1B of NTM revenue, it only requires 3% ownership in that company to return $200M. Footwork’s first fund is $175M, with average initial ownership of just under 15% in our first 11 investments, so even with dilution, if any of our portfolio companies reaches $6B in market cap, that single investment will be very likely to return the fund.

We think a lot about how a business can get to over $1 billion in revenue, at the time when we’re making the investment decision, and when we’re working with our portfolio companies. For example, can the business reach millions of customers each spending thousands of dollars per year? Or thousands of customers each spending millions of dollars per year? Or something in between? Of course, we’re not the only VCs who think this way. Venture firm Battery Ventures published a piece in 2021 about Billion-Dollar B2B companies, highlighting some of the characteristics of B2B companies that have scaled to over $1 billion in ARR.

My partner Mike has helped scale two businesses as COO to over $1 billion in revenue (Stitch Fix and Walmart.com). I’ve invested at the early-stage in one company that’s now scaled past $1 billion in revenue (Canva) and another that’s almost there (you’re welcome to try to guess which one!). Our hope is that we can partner with several more companies in the coming decades that end up achieving this goal. And our belief is that orienting around the goal of $1 billion in annual revenue is far healthier for companies than orienting around a valuation north of $1 billion.

The $1+ Billion Revenue Club

The challenge with coming up with a list of members of this club today is that not many private companies openly talk about their revenue figures. Of course, there are now-public companies in this group that belong and are worth analyzing. Companies started since 2003 that fit the bill include Tesla, Meta, ServiceNow, Uber, Airbnb, and Palo Alto Networks. PitchBook lists 78 U.S. public tech companies that have scaled to over $1 billion in revenue since being founded in 2003 with some of them having been acquired (the data has not been reviewed by PitchBook analysts, and is only available to PitchBook licensees). Below is a screenshot from Koyfin of the 64 currently public tech companies in the U.S. with revenue of over $1 billion annually.

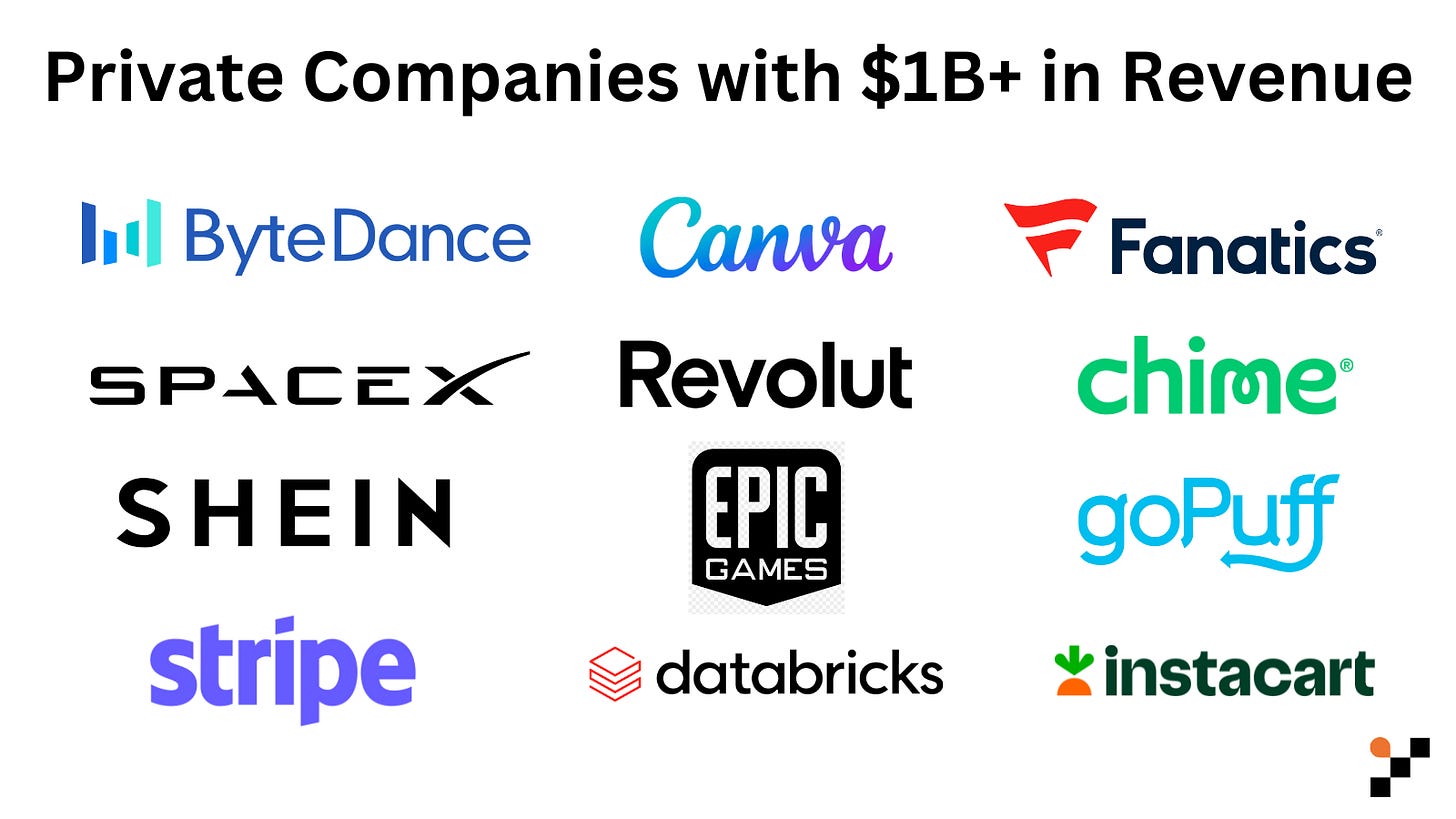

But a complete list would include those companies that are still private. Some of those are ByteDance (TikTok), SpaceX, SHEIN, Stripe, Canva, Revolut, Epic Games, Databricks, Fanatics, Chime, Gopuff, Instacart, all of which have publicly disclosed revenue figures or had reliable sources confirm that their revenues have eclipsed $1 billion annually.

This piece is not meant to come up with the complete list of companies in the billion dollar revenue club. I’ll leave that to the likes of CB Insights, Crunchbase, and PitchBook. And this isn’t an analysis of those companies (though I intend to do that one day, as I did for what Unicorns looked like at the Series A with my former partner Tod Francis back in 2015).

It's also worth acknowledging, as I did earlier in this piece, that $1 billion in revenue means something different for every company, what it recognizes as revenue (vs. gross merchandise volume, for instance), the margin profile of that revenue, the stickiness of that revenue, and more. And finally, there are incredible companies, that are not yet at or won’t get to $1 billion or more in revenue, that deserve multi-billion-dollar enterprise values and exits, for all sorts of reasons.

But my hope is that this piece can be the start of a conversation around what it means to get to over $1 billion in annual revenue, and how, as a goal post and north star, it’s much worthier than a $1 billion valuation.

P.S. I’d love to call this the Gigacorn Club, since the prefix Giga- refers to billion, and -corn is a nod to Unicorn and Decacorn. The challenge is that climate investors have used the Gigacorn term for companies that have the potential to achieve over 1 gigaton in reduction in carbon emissions 🤷🏽♂️. I’d love your ideas on what to call this group of companies.

I started next big thing to share unfiltered thoughts. I’d love your feedback, questions, and comments!

👇🏽 please hit the ♥️ button below if you enjoyed this post.

Great writeup!

Shifting from $B valuation to $B revenues is a step in the right direction. This thinking has to and will change given current economic conditions.

Taking it further, it would be more helpful if we can move to free cash flow or margins (even more indicative of a healthy business) and have a way to characterize this group.

Great post, Nikhil! As a corollary, I think Goodhart's Law is a great way to frame the misguided approach to unicorn fetishisation over the past decade (i.e. “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”).