Consumer Subscriptions

It's still early days for the increasingly dominant business model of the Internet

Welcome to issue #18 of next big thing.

Two quick announcements:

A few weeks ago, on September 9 (the day the sun didn’t rise in the San Francisco Bay Area), I participated in a panel on the future of venture capital at AngelList Confidential, alongside Helen Min of AngelList, Bobby Goodlatte of Form Capital, and Brianne Kimmel of Worklife Ventures. Here is a recording of the conversation.

This coming Friday, I’ll be recording a live episode of Founders & Funding with Jonathan Regev, co-founder and CEO of The Farmer’s Dog*. I led the company’s Series A in 2017, and have been working with Jonathan and team since. This should be a fun conversation. Join us live by registering here.

On to this week’s essay:

Many of the companies I’ve invested in, including The Farmer’s Dog, are subscription businesses. I’ve written a bit about subscriptions in the past — from this post on Dollar Shave Club’s retention to a pre-IPO analysis of Blue Apron to announcements of my investments in Imperfect*, Literati* and others — but never a cohesive set of thoughts about the subject.

This is the first in a series of three essays on consumer subscriptions.

Today, I’ll give you a quick overview of how I think about this category. The next piece will dive into the factors that I consider in evaluating these businesses (Part 2). And the final one will be a case study on one of my investments (Part 3).

As always, I’d love your feedback throughout. Please leave a comment, and subscribe if you wish to receive every new essay directly in your inbox.

Digital and Physical Subscriptions

Everywhere I look, it feels like there’s a subscription service lurking.

From the news I read to the music I listen to, from software for taking notes to cloud storage for documents and photos, from food delivery to delivery of anything, from workouts to TV shows, and from insurance to utilities, so many of my purchases are recurring and auto-renewing via a subscription.

Of course, this is not a new insight, nor a new business model. Subscription services such as the cable bundle are decades-old.

The Internet, though, has enabled the bundling of services into broad subscriptions, as well as the unbundling of services into niche subscriptions, possible for a wide variety of businesses to offer.

Most of the large technology companies have subscription offerings. Microsoft’s* subscription products include 365 and Xbox Game Pass. Amazon* has Prime, Subscribe & Save, Audible and more. Apple* offers hardware such as iPhones for purchase on a monthly subscription, software such as its newly launched Apple One bundle, and enables developers to sell subscriptions through the App Store. Google* has Drive, YouTube Premium, developer subscriptions through Google Play, and more. Facebook* has launched subscription groups and fan subscriptions. Netflix* is entirely subscription-based.

Subscription is also at the heart of many startups’ business models, across most areas of consumer spend.

One way to segment subscription businesses is to divide them between purely digital subscriptions and subscriptions with physical products. Take the fitness category, for instance. Digital subscription businesses in fitness include Future, Strava, and Zwift*. You interact with these services purely on your digital devices. Physical subscriptions in fitness include delivery of products such as Fabletics and Musclebox, and in-person experience-based fitness subscriptions such as gym memberships, group fitness workouts like Barry’s Bootcamp, or subscription bundles like ClassPass. Finally, there are hybrid digital-physical subscription businesses like Peloton and Tonal*, where you pay for the physical hardware (either upfront or on monthly basis) as well as a digital content subscription.

Digital and physical subscriptions can be very different businesses — different marginal costs of delivering the subscription service, different friction in customer acquisition and in ongoing retention, different operationally, and therefore they can be valued very differently as multiples of revenue and profit.

But huge businesses can be built in physical, digital, and hybrid subscriptions. Much of Chewy’s business is physical subscription for pet products, and it’s currently valued at $23 billion in the public markets. Peloton is worth $27 billion. And Spotify*, a digital subscription business for music, is worth $43 billion.

And a lot of the business and consumer behavior characteristics are similar across these different types of subscription businesses. I’ve seen this firsthand from having invested in digital subscriptions like Canva* and ClassDojo* and physical subscriptions like Pill Club* and The Farmer’s Dog*. So as I continue to write about consumer subscriptions, I’ll refer to both digital and physical subscriptions, and share learnings that I believe are applicable to building both.

Still A Small Fraction of Consumer Spend

Of course, a natural question given the number of subscription businesses that are out there is “have we hit peak subscription?”

According to an analysis earlier this year by Mint.com for the New York Times, each of us in the U.S. spent on average $640 on digital subscriptions in 2019, up from $598 in 2017.

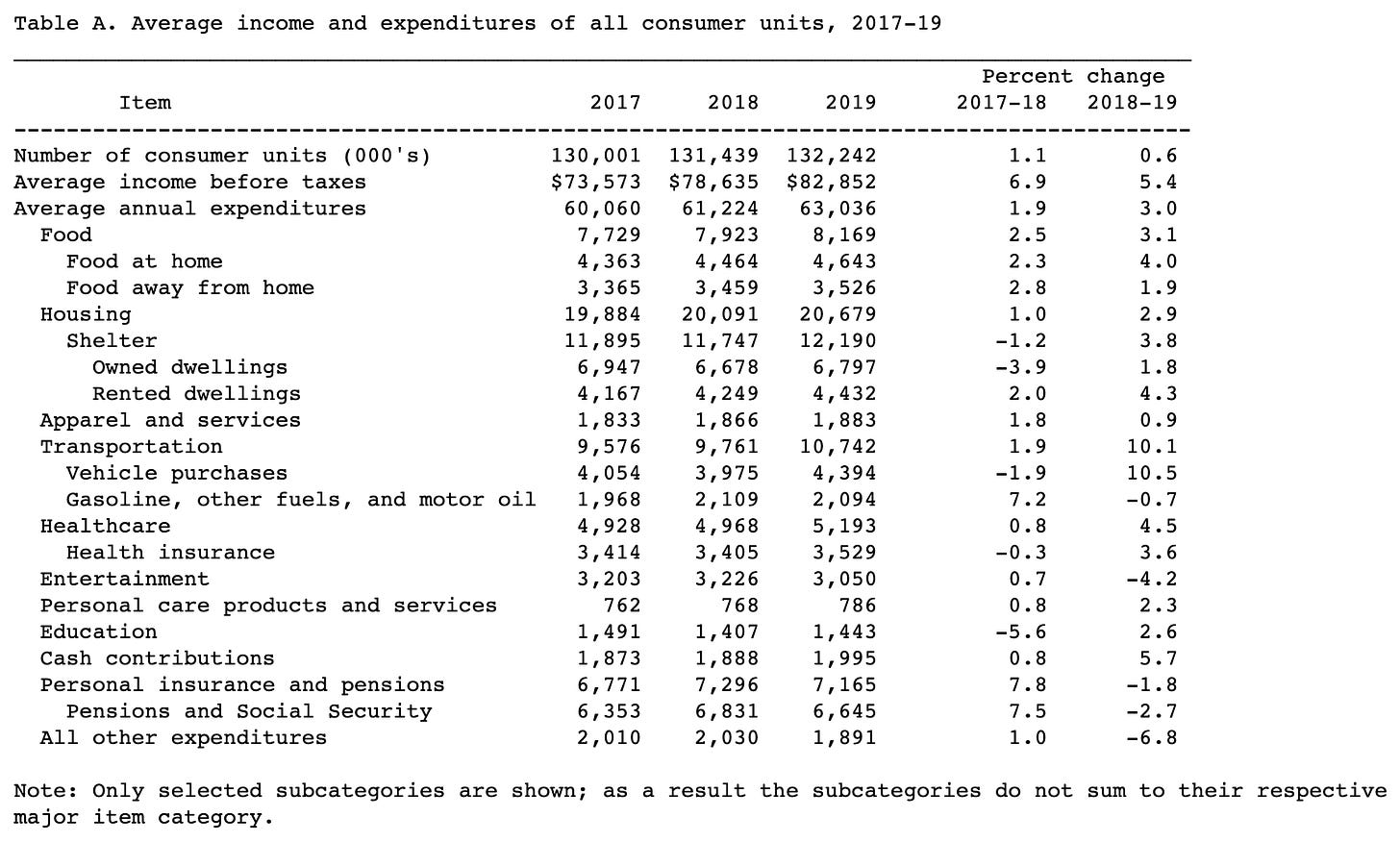

With an average household spend of $63,036 in 2019, and an average of 2.52 people per household, the $640 spend on digital subscriptions represents 2.55% of an individual’s annual expenditures.

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics on Consumer Expenditures from 2017 to 2019.

When you look beneath the surface at where the average person spends their money, you see the many opportunities for subscriptions, as well as the existing subscription characteristics of a lot of spend. Housing is effectively already a “subscription” via mortgages or rent for most people. For those who lease vehicles, the bulk of Transportation spending is subscription spending. As I discussed in #13 and #15, the restaurant and grocery businesses are fundamentally changing due to covid-19, delivery and other characteristics, presenting an opportunity for more of Food spending to be on a subscription basis. Businesses like Stitch Fix and Dollar Shave Club have subscription-ized apparel and personal care respectively.

I could go on across every category of spend. The natural counter-perspective to the growth of subscriptions is that consumers are getting tired of subscribing for everything, and there will be backlash against this. Subscription fatigue isn’t something I’ve spent time agonizing over, in part because the qualitative and quantitative data suggests that consumers are adopting more subscription services than ever before, and are happy subscribers!

Matthew Ball wrote a fantastic piece on subscription fatigue that eloquently summarizes many of my sentiments about the subject. It’s worth reading the whole essay, but here’s a section that very much resonated:

The “subscription economy”, by definition, presumes that the overall “economy” – from products, to services, content, transportation, labor and more – is shifting over to “subscriptions”. Thus, to claim that consumers have “subscription fatigue” is to say that they have “spending fatigue”.

As always, most consumers will say they wish they spent less money, bought fewer things, and enjoyed lower prices. However, it makes little sense to say that the decision to buy TV subscriptions, radio subscriptions, toothbrush subscriptions, video gaming subscriptions, dog food subscriptions, car subscriptions, or productivity software subscriptions should drive “subscription fatigue” or mean each subscription competes with one another. For decades, consumers have bought TV, music, toothbrushes, video games, dog food, cars and Microsoft Office. What’s new is that they all have similar models – digitally-based, predominantly D2C subscriptions. This changes nothing about the individual value or baseline need for them.

Of course, the “subscription economy” does mean that step one of a recession will be to “re-evaluate all subscriptions”. However, this does not mean subscription fatigue should be considered a real “thing”, let alone a defining element of modern-day competition. Furthermore, payment model – upfront v. recurring, subscription v. á la carte, online v. offline – is irrelevant to what’s “re-evaluated” and not. Some subscriptions are “necessities”, like toilet paper, while others are concerned with discretionary spend, such as Office 365 or Netflix or Tinder. This latter group isn’t competitive because they’re “subscriptions”, but because there is, as always, finite spending money for non-essential items.

To this end, it’s important to highlight subscriptions are often a preferred buying path for consumers.

I couldn’t agree more with Matthew. Subscriptions are here to stay, particularly for products and services that are “must haves.”

An Increasingly Dominant Business Model

If the first 20 years of the Internet, from 1995-2015, was defined by advertising- and marketplace-based business models, it feels clear that the current era, perhaps beginning around 2015, is defined by the subscription business model.

There are two more data points that make me confident that subscription businesses will continue to proliferate in the years ahead.

First, across my portfolio of subscription investments, growth in 2020 has been astounding, and well ahead of plan. As many have noted, covid-19 has accelerated trends that were already underway pre-pandemic. In eCommerce broadly, and in categories such as content, education, fitness, food, and healthcare, consumers seem to be gravitating toward subscriptions more than ever before. This insight isn’t unique to my portfolio; just look at the public markets and some of the companies I’ve mentioned in this post, many of which are trading at record enterprise values on the back of record growth quarters.

Second, many of the business-in-a-box (BiaB) platforms, such as Shopify and Substack, are enabling new businesses to be started and grown, and many of the businesses built on these platforms are subscription businesses. The BiaB platforms are experiencing tailwinds, the businesses they enable are expanding too, and in the process consumers are getting more and more used to buying everything as a subscription.

That the next big thing is a consumer subscription business is perhaps the most obvious statement I’ve made since starting this newsletter. I’m excited to dive further into this topic in the weeks ahead.

Here’s some great further reading on consumer subscriptions:

The Flaws of "Subscription Fatigue", "SVOD Fatigue", and the "Streaming Wars" by Matthew Ball (2020)

The State of Consumer Subscriptions by Brett Bivens (2019)

The continuous rise of SaaS in the consumer space by Angela Tran (2019)

Is Consumer Subscription the Next Software Boom market? by Eric Crowley (2019)

Consumer Subscription Software Insights by GP Bullhound (2019)

Consumer Subscription Software by Nico Wittenborn (2016)

Mass SaaS: Thinking about SaaS on the Consumer Side by Zal Bilimoria (2015)

The Internet Subscription Startup is Winning by Tom Tunguz (2013)

I started next big thing to share unfiltered thoughts. I’d love your feedback, questions, and comments!

*denotes a company I'm affiliated with as an investor - see my substack about page.

Unfortunately I messed up the link for the AngelList Confidential conversation when this post went out to all subscribers. Here's the correct link to the video recording: https://vimeo.com/456778040/130bfb1cda

Hey Nikhil,

had a small question about subscriptions: why do annual subscriptions only work by paying the complete amount upfront? (It could maybe have a simpler answer, but I haven't found it yet)